Our Freediving Ancestors

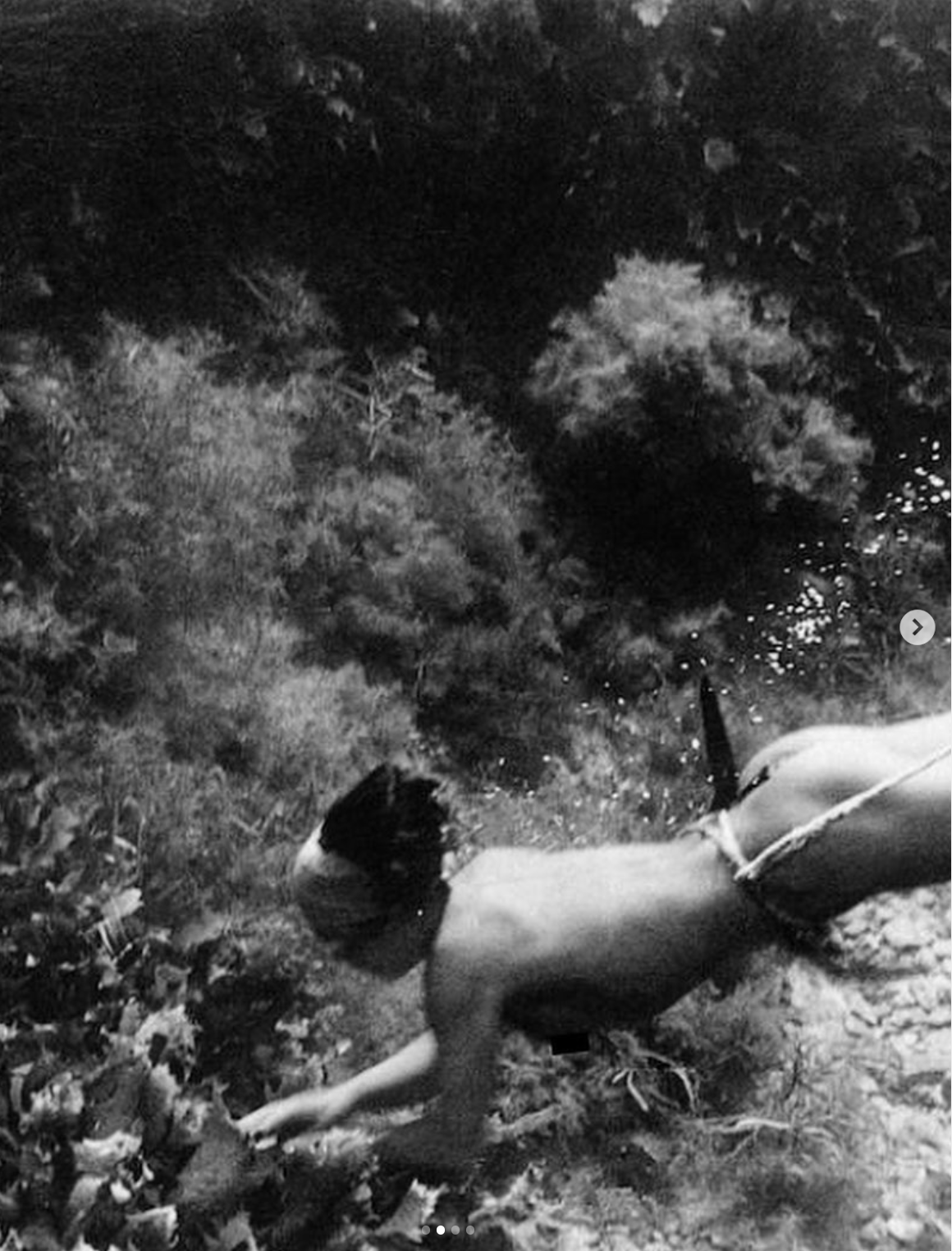

Freediving is so much more than how it can be represented today; fancy bubble rings, depth records, hot girls and long fins…It was a true art form, a true way of life and survival (still is!) The men and women endured harsh conditions. They put up with ill equipped gear. But oh did they do it in style! Not to mention without fins most of the time! These are our ocean hero’s.

There are still a handful of traditional freediving communities around the world, the Haenyeo or sea women of Juju Island, South Korea, the Bajau and Moken peoples (sea gypsies/sea nomads) of South East Asia and the Japanese Ama.

About 2000 years ago the Ama (the coastal people of Japan) began to dive for seafood, abalone and pearls, with official records of these sea women dating back to 927 AD. They were honoured with the task of collecting abalone for shrines and imperial emperors. These sea women of Japan still freedive today collecting seaweed, shellfish, sea urchins, pearls, and abalone to sell at the market. The Ama are a matriarchal commune; girls start learning to dive from a young age and are guided by their more experienced elders who remain active divers well into their 70s. Being an Ama diver is not something you can decide to become, it’s hereditary with rights and training handed down from mother to daughter.

The majority of Ama are women the most common theory for why this is lies in their tendency to have an extra layer of fat on their bodies to insulate them from cold water and their ability to hold their breath longer. Being an Ama enabled many women to be self-supporting as it was one of the top kinds of work.

Traditionally, the Ama dived wearing only a white loincloth or *fundoshi,* allowing them to move more freely and efficiently in the water; they covered their hair with a *tenugi* or bandana. To keep them connected to the boat while they were in the water they tied a rope around their waists which they tugged on when they were ready to resurface. More recently, to cover their modesty, Ama have adopted white cotton garments and some have embraced more modern wetsuits.

There were once thousands of Ama but as fewer girls follow in their mothers footsteps their numbers have drastically dropped in recent years.

Featured photos below; by Fosco Maraini and Eishin Osaki

There’s so much history within the freediving world and I love learning more about the pioneers of this sport. Those that have relied on freediving for their livelihood and have become one with their ocean surrounds.

The Bajau also known as sea gypsies or sea nomads, are an ethnic group of maritime southeast Asia. They have lived at sea for over 1000 years on small houseboats off Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Over many generations the Bajau people have developed remarkable adaptations to their underwater lifestyle:

🤿 Superior breath-holding ability: Studies have shown that the Bajau have larger spleens than non-diving populations, which may store more oxygenated red blood cells and release them when needed. This contributes to the Bajau being able to dive up to 70 meters deep and stay submerged for several minutes without any scuba gear.

👀 Better underwater vision: It is thought that a genetic adaptation allows the Bajau to constrict their pupils more, reducing the amount of light entering their eyes and improving focus is behind their visual acuity being twice as sharp as Europeans when underwater!

👂 Enhanced hearing: The Bajau can detect low-frequency sounds more easily than non-divers, which may help them locate fish and avoid predators. Research suggests this may be linked to physical changes in the ear, such as a more flexible eardrum.

On Jeju Island, South Korea, live a community of women who freedive for up to 7 hours a day, 90 days of the year, harvesting marine life such as shellfish and seaweeds. They were first recorded harvesting abalone in 1629 and there is evidence that they were diving centuries before this.

As of 2011, there were about 5000 Haenyeo on Jeju Island, most of whom were over 60 with some in their 80s. At their peak in the 1960s, there were around 30,000. Traditionally, girls and young women would train under their elders, learning to harvest conch, sea cucumber, urchins, abalone and seaweed, diving in icy cold to warm waters, on both calm and days and days when the ocean conditions are less than ideal. Harvesting off the coast of Jeju is dangerous physical work and the job the Haenyeo do in the sea is called Muljil the methods for this are gotmuljil referring to going out to the sea from the shore, baetmuljil, going out to the sea by boat, and, the nabar, which refers to sailing for days on a ship moving and diving from one island to the next.

The nature by which the Haenyeo harvest the sea is very sustainable. They have a rich knowledge of their fishing grounds, the sea geography, tides, winds and sea creatures. With this knowledge, they can estimate seasonal marine life's growing cycles and outputs and harvest them accordingly, from knowing the best time to harvest agar-agar each year to not harvesting conches and abalone during their spawning season. Haenyeo pass their rich knowledge and vast experience from one generation to the next. Today, the Haenyeo women are recognised by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

📸 Brian Miller, Amanderson an John Ko